The Universe as One Mind: Spinoza's Radical Vision

Have you ever looked up at the night sky and felt a strange sense of connection—as if you and the stars were part of something larger, something unified? That feeling might be closer to philosophical truth than you think. In the 17th century, a lens-grinding philosopher named Baruch Spinoza proposed something so radical it got him excommunicated from his community: the idea that everything in existence—from your morning coffee to distant galaxies—is part of one infinite substance, and that this substance has both physical and mental aspects.

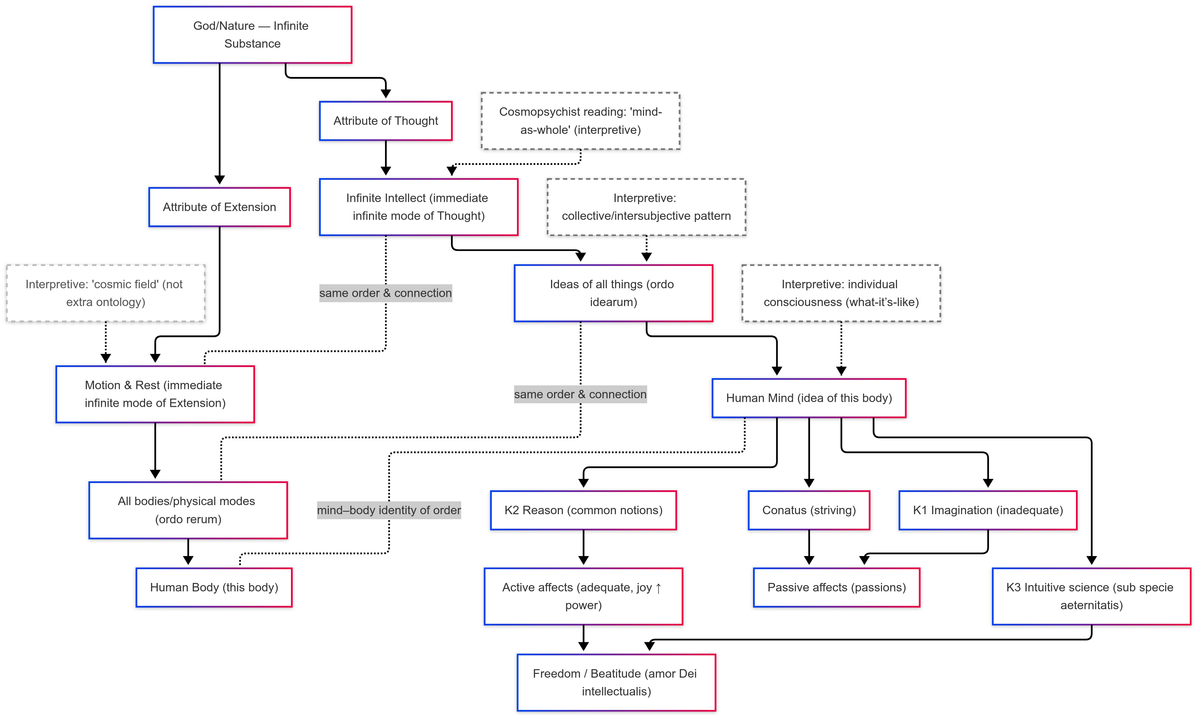

Today, as neuroscientists grapple with the "hard problem" of consciousness and physicists probe the fundamental nature of reality, Spinoza's vision is experiencing a remarkable renaissance. Contemporary philosophers like Philip Goff and David Chalmers are seriously considering panpsychist interpretations that echo Spinoza's insights. Let's explore this fascinating philosophical landscape through a diagram that maps the architecture of reality according to Spinoza's Ethics.

The Foundation: One Substance, Infinite Expressions

At the top of our diagram sits "God/Nature—Infinite Substance." For Spinoza, these aren't separate entities but different names for the same reality. Imagine reality as an infinite ocean—everything that exists is like waves, currents, and whirlpools within this ocean. The waves aren't separate from the ocean; they're expressions of it.

This substance expresses itself through what Spinoza calls "attributes"—fundamental ways of being. Our diagram shows two: the Attribute of Thought and the Attribute of Extension (physical reality). Think of these as two languages describing the same book. Every event has both a mental description ("I'm thinking about pizza") and a physical description ("neurons are firing in specific patterns"). They're not separate events but the same event described in two ways.

The Cosmic Mind and Cosmic Body

Moving down our diagram, we encounter something extraordinary: immediate infinite modes. In the realm of thought, this is "Infinite Intellect"—what some contemporary philosophers interpret as a kind of cosmic consciousness or "mind-as-whole." In the physical realm, it's "Motion & Rest"—the fundamental patterns that govern all physical interactions.

Here's where it gets fascinating for modern readers: this isn't just abstract metaphysics. Consider how quantum field theory describes reality as patterns of excitation in underlying fields, or how information theory suggests that information might be more fundamental than matter. Spinoza's "cosmic field" interpretation, shown in our diagram's interpretive overlays, resonates with these contemporary insights.

From Cosmos to Human: The Nested Reality

The diagram then shows how cosmic patterns give rise to finite modes—the "ordo idearum" (order of ideas) and "ordo rerum" (order of things). This is where individual minds and bodies emerge from the cosmic fabric. Your mind isn't separate from the universal mind; it's a particular pattern within it, like a melody within a symphony.

Consider Sarah, a marine biologist studying coral reefs. When she observes the intricate ecosystem, her individual consciousness (what philosophers call "what-it's-like-ness") is simultaneously a local pattern in the cosmic mind and perfectly correlated with specific neural patterns in her brain. The dashed lines in our diagram represent this "parallelism"—mind and body aren't separate substances interacting, but the same reality viewed from different perspectives.

The Journey of Knowledge and Freedom

The lower portion of our diagram maps Spinoza's epistemology and ethics—how we know and how we should live. Spinoza identified three kinds of knowledge: imagination (often inadequate and based on random experience), reason (which grasps universal patterns and "common notions"), and intuitive knowledge (direct insight into the eternal nature of things).

Here's a story that illustrates this progression: Maria, a climate scientist, begins with imagination—scattered observations about weather patterns. Through reason, she develops mathematical models that reveal underlying climate dynamics. Finally, through intuitive knowledge, she grasps the deep interconnectedness of Earth's systems "sub specie aeternitatis"—from the perspective of eternity.

This journey of knowledge is intimately connected to ethics. As we understand our place in the cosmic web, we move from passive emotions (being pushed around by external forces) to active emotions (acting from our own nature in harmony with the whole). The ultimate goal is what Spinoza calls "amor Dei intellectualis"—the intellectual love of God/Nature—a state of freedom and beatitude that comes from understanding our unity with everything.

Contemporary Echoes: Why This Matters Now

Why should we care about a 17th-century philosopher's cosmic vision? Because Spinoza's insights anticipate some of the most pressing questions in contemporary science and philosophy. The "hard problem" of consciousness—how subjective experience arises from objective processes—dissolves if consciousness is fundamental rather than emergent. Environmental crises become not just practical problems but violations of our deepest nature as parts of an interconnected whole.

The interpretive overlays in our diagram—the dotted lines connecting cosmic consciousness to infinite intellect, collective patterns to the order of ideas—represent how contemporary panpsychist philosophers are updating Spinoza's vision. They're not adding new ontological entities but offering new ways to understand the mental aspect of reality that Spinoza insisted was always there.

Living the Vision

Spinoza's philosophy isn't just intellectual exercise—it's a way of life. When you truly grasp that you're not a separate self struggling against an alien universe but a unique expression of the universe coming to know itself, everything changes. Your joys become the universe celebrating through you; your sorrows become the universe grieving through you; your insights become the universe understanding itself more deeply.

This doesn't lead to passive fatalism but to what Spinoza calls "active affects"—emotions and actions that flow from understanding rather than confusion. When Maria the climate scientist acts to protect the environment, she's not imposing her will on nature but expressing nature's own drive toward greater perfection and complexity.

The practical takeaway is both simple and profound: pay attention to the connections. Notice how your thoughts and feelings are part of larger patterns. Recognize that understanding these patterns—whether through science, philosophy, or contemplative practice—is itself part of the universe's ongoing self-discovery. As you develop what Spinoza calls "common notions"—insights into what you share with other beings—you naturally become more compassionate and effective.

In our age of fragmentation and alienation, Spinoza offers a vision of radical belonging. You are not a stranger in a strange land but the universe itself, awakening to its own infinite nature through the particular lens of your experience. The question isn't whether this vision is true—the question is what happens when you live as if it were.

What would change in your daily life if you truly experienced yourself as a wave in the infinite ocean of being?

Further Reading

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Baruch Spinoza - Comprehensive overview of Spinoza's philosophy and its contemporary relevance

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Panpsychism - Detailed exploration of contemporary panpsychist theories and their connection to historical precedents

- Panpsychism: Contemporary Perspectives - Collection of recent philosophical work on panpsychism and consciousness

- Philosophy Now: The Case For Panpsychism - Accessible introduction to contemporary arguments for panpsychist theories of mind