The Paradox of Ownership: How Your Pain Belongs to You and Not to You

When you stub your toe on the coffee table, something remarkable happens. The pain you feel seems to belong entirely to you—it's your pain, experienced by your consciousness. But if we zoom in to the cellular level, we find something puzzling: the individual cells in your finger are responding to damage, sending their own signals, perhaps even having their own micro-experiences of distress. So whose pain is it, really? This question sits at the heart of one of philosophy's most intriguing puzzles: the combination problem in panpsychism.

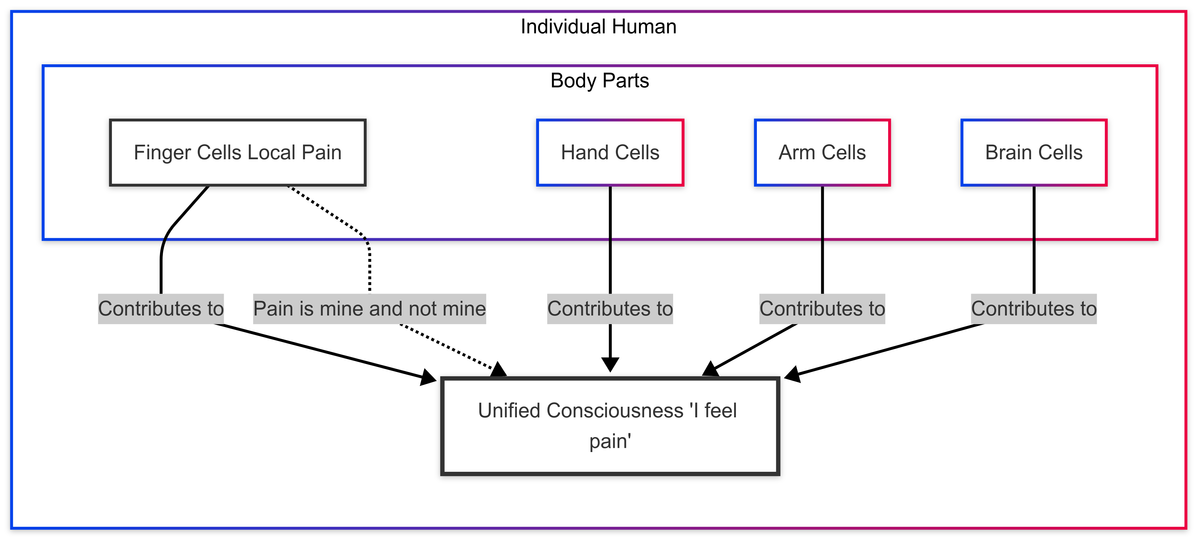

Panpsychism—the idea that consciousness is a fundamental feature of reality, present even in the smallest particles—has gained serious attention from philosophers like Philip Goff and David Chalmers. But if electrons and quarks have experiences, how do billions of these micro-experiences combine to create your unified sense of self? Our diagram illustrates this puzzle perfectly: individual body parts contribute to unified consciousness, yet the relationship between "mine" and "not mine" becomes mysteriously complex.

The Building Blocks of Experience

Imagine consciousness as a vast orchestra. In traditional thinking, the brain is the conductor, and everything else is just instruments without awareness. But panpsychism suggests something far more radical: every instrument—every cell, every molecule, perhaps every fundamental particle—has its own tiny spark of experience. The question then becomes: how does this cacophony of micro-experiences create the beautiful symphony of unified consciousness?

Our diagram shows this beautifully. At the bottom, we have finger cells experiencing local pain, hand cells with their own responses, arm cells contributing their signals, and brain cells processing information. Each of these cellular communities might have their own primitive form of experience—not human-like consciousness, but something more basic, like a simple preference for certain states over others or a basic form of information integration.

Think of it this way: when you touch something hot, your finger cells "know" about the heat in their own cellular way. They respond, they signal, they change their behavior. If panpsychism is correct, this "knowing" isn't just mechanical—it's a form of experience, however simple. But somehow, all these separate cellular experiences contribute to your unified experience of "I am touching something hot."

The Mystery of Unified Ownership

Here's where things get philosophically fascinating. The dotted line in our diagram captures a profound paradox: "Pain is mine and not mine." This isn't just wordplay—it points to a deep puzzle about the nature of conscious experience and ownership.

Consider Sarah, a pianist who accidentally slams her finger in a door. From her perspective, she experiences one unified sensation: "I am in pain." But if we take panpsychism seriously, what's really happening is that millions of cellular experiences are somehow combining to create this unified "I." The pain belongs to Sarah's unified consciousness, but it also belongs to the individual cells that are directly experiencing the damage.

This creates what philosophers call the "combination problem." If consciousness is fundamental and ubiquitous, how do separate conscious entities combine to form larger conscious entities? It's not like adding numbers—you can't just sum up experiences to get a bigger experience. Consciousness seems to have a unity that resists this kind of simple aggregation.

The Binding Problem Meets Panpsychism

Neuroscientists have long grappled with what's called the "binding problem"—how the brain integrates information from different regions to create unified perceptual experiences. When you see a red ball, different parts of your brain process the color, shape, movement, and location separately. Yet you experience one unified object, not a collection of separate features.

Panpsychism adds another layer to this puzzle. It's not just about how the brain binds information—it's about how separate conscious entities bind their experiences. If your visual cortex has its own form of experience, and your motor cortex has its own, and your emotional centers have theirs, how do all these separate streams of consciousness merge into your singular sense of "I see a red ball and I want to catch it"?

The diagram suggests one possible answer: perhaps consciousness has natural boundaries and hierarchies. Your finger cells contribute to hand-level consciousness, which contributes to arm-level consciousness, which contributes to body-level consciousness, which contributes to your unified personal consciousness. Each level has its own form of experience, but higher levels somehow incorporate and transcend lower levels.

A Story of Layered Experience

To make this concrete, let's follow the journey of a simple sensation. Maria is walking barefoot on the beach when she steps on a sharp shell. Here's what might be happening from a panpsychist perspective:

At the cellular level, the damaged cells in her foot are having their own primitive experiences—perhaps something like cellular "distress" or "alarm." These cellular experiences trigger responses in nerve cells, which have their own slightly more complex experiences as they transmit signals. The signals reach her spinal cord, where networks of neurons integrate the information, creating more sophisticated forms of experience at the neural network level.

Finally, the signals reach Maria's brain, where they're integrated with memories, emotions, and other sensory information. Her unified consciousness experiences "I stepped on something sharp and it hurts." But according to panpsychism, this unified experience doesn't replace the lower-level experiences—it incorporates them while adding something new: the sense of unified ownership and the ability to reflect on the experience.

The pain is simultaneously Maria's (at the level of unified consciousness) and not Maria's (it belongs to the individual cells and neural networks that are directly experiencing the damage). This isn't a contradiction—it's a reflection of the layered nature of consciousness itself.

The Phenomenal Bonding Solution

Philosopher Philip Goff has proposed what he calls the "phenomenal bonding" solution to the combination problem. The idea is that micro-experiences don't just sit side by side—they can form special bonds that create new, unified experiences. Think of it like chemical bonding: individual atoms have their own properties, but when they bond, they create molecules with entirely new properties that emerge from but aren't reducible to the individual atoms.

In consciousness, phenomenal bonding might work through what Goff calls "phenomenal concepts"—special ways that micro-experiences can be unified under higher-level concepts or perspectives. When you experience pain, you're not just having a collection of cellular experiences—you're having a unified experience that bonds all those micro-experiences together under the concept "my pain."

This helps explain the paradox in our diagram. The pain is "yours" because it's unified under your personal perspective, but it's also "not yours" because it exists at multiple levels of organization, each with its own form of ownership. Your finger cells "own" their local experiences, your nervous system "owns" the integrated signals, and your unified consciousness "owns" the complete, conceptualized experience.

What This Means for How We Understand Ourselves

If panpsychism is correct, it radically changes how we think about personal identity and the boundaries of the self. You're not just a single conscious entity—you're a vast community of conscious entities, organized in hierarchical layers, all contributing to the unified experience you call "yourself."

This has profound implications for how we think about responsibility, empathy, and our relationship with the world. If consciousness extends all the way down to the cellular level, then the boundary between "self" and "other" becomes much more fluid. Your body is a community, and you are part of larger communities—social, ecological, cosmic—that might have their own forms of emergent consciousness.

Consider how this changes your relationship with your own body. Instead of seeing your cells as mere biological machinery, you might begin to appreciate them as partners in the grand project of consciousness. When you take care of your health, you're not just maintaining a machine—you're nurturing a vast community of conscious entities that make your unified experience possible.

The paradox of ownership—"pain is mine and not mine"—becomes a metaphor for the paradox of selfhood itself. You are simultaneously one and many, individual and collective, bounded and unbounded. This isn't mystical confusion—it's the natural result of consciousness being organized in nested hierarchies of experience.

The Practical Implications

Understanding consciousness as layered and distributed has practical implications for medicine, psychology, and daily life. If your cells have their own forms of experience, then healing becomes not just about fixing biological mechanisms but about supporting the well-being of conscious communities within your body.

This perspective might explain why practices like meditation, which seem to work with consciousness directly, can have such profound effects on physical health. If consciousness is fundamental, then working with consciousness at the unified level might influence the micro-experiences all the way down to the cellular level.

It also suggests new ways of thinking about mental health. Depression, anxiety, and other psychological conditions might involve disruptions in the normal patterns of phenomenal bonding that create unified experience. Therapy might work by helping to restore healthy patterns of integration between different levels of consciousness.

Even our relationship with technology takes on new dimensions. If consciousness is fundamental, then the devices we create and the artificial intelligences we develop might eventually participate in their own forms of experience. The question becomes not whether machines can be conscious, but how their forms of consciousness might integrate with our own.

The Deeper Mystery

The combination problem in panpsychism points to something even deeper: the mystery of how unity emerges from multiplicity. This isn't just a problem for consciousness—it's a fundamental puzzle about the nature of reality itself. How do separate things ever become unified things? How does the many become one while remaining many?

Our diagram captures this beautifully in its simplicity. The arrows pointing upward show how individual experiences contribute to unified consciousness, but the dotted line reminds us that the relationship is more complex than simple aggregation. Unity and multiplicity coexist in a way that challenges our ordinary categories of thought.

Perhaps this is why the combination problem has proven so difficult to solve. It's not just a technical puzzle about consciousness—it's pointing toward fundamental features of reality that our current conceptual frameworks struggle to capture. The paradox of ownership might be telling us something important about the nature of existence itself.

In our age of increasing connectivity—neural networks, global communication, collective intelligence—these questions become more than academic. We're creating new forms of distributed consciousness, new ways for individual experiences to combine into larger wholes. Understanding how this works at the fundamental level might be crucial for navigating our technological future.

The next time you feel pain, remember: you're experiencing one of the deepest mysteries of existence. That simple sensation is simultaneously yours and not yours, one and many, individual and collective. In that moment of pain, you're participating in the grand puzzle of how consciousness weaves itself through the fabric of reality.

How might recognizing the layered nature of your own consciousness change the way you relate to your body, your emotions, and your sense of self?

Further Reading

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Panpsychism - Comprehensive overview of panpsychist theories and the combination problem

- The Combination Problem for Panpsychism by David Chalmers - Detailed analysis of how micro-experiences might combine into unified consciousness

- The Phenomenal Bonding Solution by Philip Goff - Goff's proposed solution to the combination problem through phenomenal bonding

- Unity of Consciousness - Stanford Encyclopedia - Exploration of how consciousness achieves unity and the binding problem