The Ancient Logic That Still Moves Us Today

Watch a child push a toy car across the floor, and you're witnessing one of philosophy's oldest puzzles in action. The car rolls forward, slows down, and eventually stops. Simple enough, right? But this everyday scene contains a mystery that kept ancient thinkers awake at night: What makes things move, and what keeps them moving?

More than two millennia ago, philosophers grappled with this question in ways that might surprise you. Their insights, captured in the logical flow of an ancient argument, reveal something profound about the nature of motion itself—and perhaps about the spark of life that animates everything around us.

The Two Faces of Motion

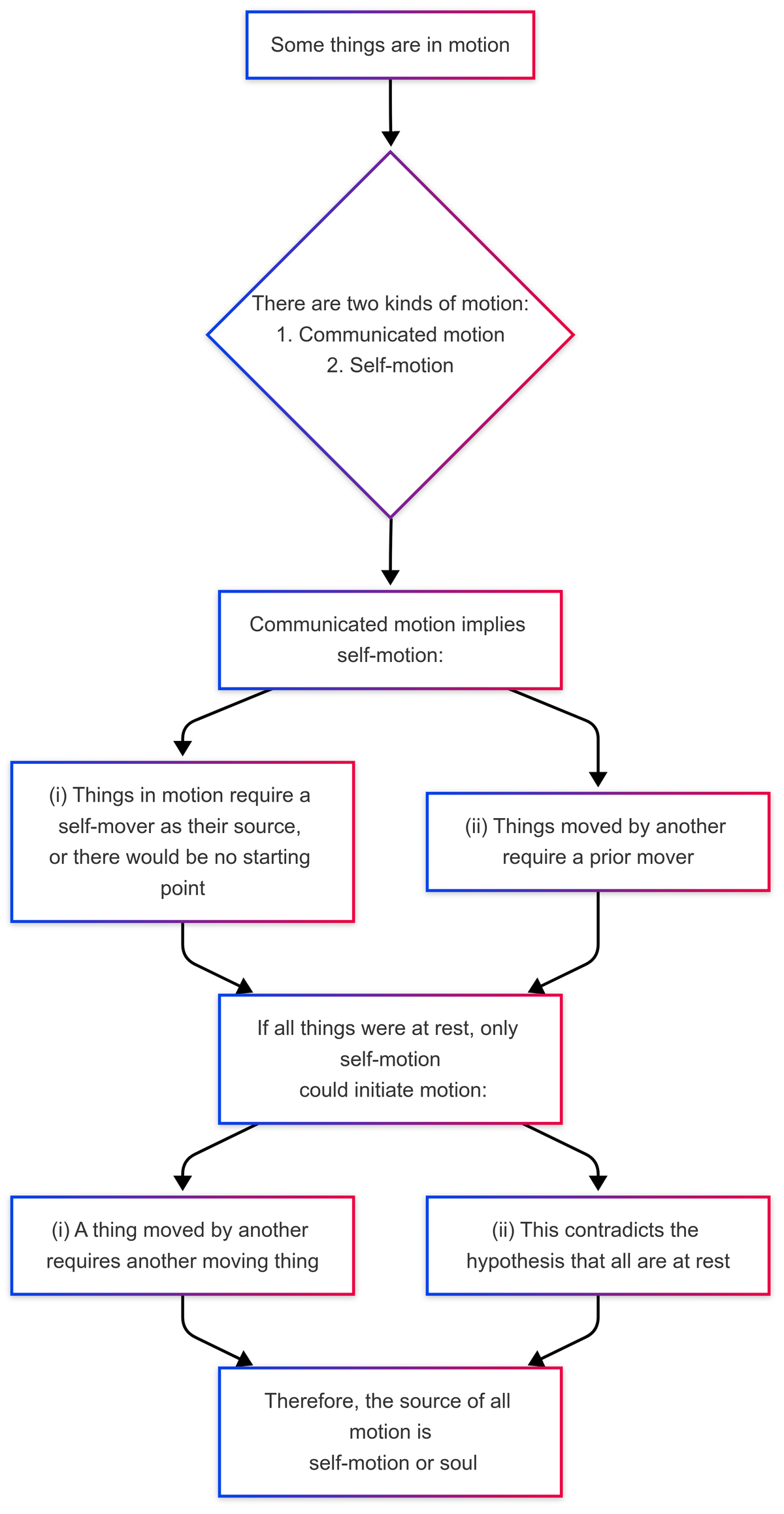

The ancient argument begins with a simple observation: some things are in motion. Look around you right now. Your heart beats, your lungs expand and contract, cars pass by your window, the Earth spins on its axis. Motion is everywhere.

But here's where it gets interesting. The philosophers noticed that motion comes in two distinct flavors. First, there's communicated motion—the kind we see when one thing pushes another. When you kick a soccer ball, you're communicating motion to it. The ball doesn't decide to move; it's compelled by the force of your foot.

Then there's self-motion—the mysterious ability of some things to move themselves. A bird takes flight not because something pushes it, but because something within it initiates the movement. A plant grows toward sunlight through its own internal drive. You decide to stand up and walk to the kitchen, and somehow, that decision translates into coordinated muscle movements.

The Chain of Movers

Here's where the ancient logic becomes fascinating. If we trace any communicated motion backward, we discover something remarkable. That soccer ball you kicked was set in motion by your foot. Your foot was moved by your leg muscles. Your muscles were activated by nerve signals. Your nerves fired because of a decision in your brain.

But we can't trace this chain backward forever. At some point, we must reach something that moves itself—a self-mover. Otherwise, we'd have an infinite regress of movers, each depending on another, with no ultimate source. It's like trying to understand why a line of dominoes fell without there being a first domino that was actually pushed.

The philosophers realized that things in motion require a self-mover as their ultimate source, or there would be no starting point for motion at all. Every chain of communicated motion must eventually trace back to something that can move itself.

The Thought Experiment

To drive this point home, the ancient thinkers proposed a thought experiment. Imagine, they said, that all things in the universe were at rest—completely motionless. In such a world, what could possibly initiate motion?

It couldn't be communicated motion, because that requires something already moving to do the communicating. A motionless thing can't push another motionless thing into motion—that would violate the very premise of our thought experiment. The only possibility would be self-motion: something would have to move itself.

This reveals a profound truth. Even in a hypothetical world of complete stillness, only self-motion could break the spell of inertia. Communicated motion, by its very nature, depends on motion already existing somewhere in the system.

A Story of Two Gardens

Let me tell you about Maria, a gardener who tends two very different plots. In her first garden, she has installed an elaborate system of mechanical sprinklers, timers, and automated tools. Everything moves according to predetermined schedules and mechanical forces. Water flows through pipes because pumps push it. Sprinkler heads rotate because gears turn them. Seeds get planted because machines drop them at programmed intervals.

In her second garden, Maria works differently. She plants seeds that grow toward the light through their own internal drive. She tends flowers that open and close according to their own rhythms. She watches birds that choose to visit, not because they're mechanically compelled, but because something within them seeks the nectar and seeds.

Both gardens are beautiful, but they represent fundamentally different types of motion. The first garden runs on communicated motion—each movement traced back to Maria's initial programming and the electrical energy powering the system. The second garden pulses with self-motion—countless individual decisions and internal drives creating a symphony of autonomous movement.

The ancient philosophers would say that even Maria's mechanical garden ultimately depends on self-motion: her decision to create it, the life force that generated the electricity powering it, and the countless self-moving processes that maintain the entire system.

The Soul of Motion

This brings us to the argument's profound conclusion: the source of all motion is self-motion, which the ancients identified with soul. Now, before you picture ghostly spirits floating around, understand that "soul" here means something more fundamental—the principle of self-movement itself.

In this view, anything capable of genuine self-motion possesses soul in some form. Your ability to decide to move your hand demonstrates soul. A plant's capacity to grow toward light reveals soul. Even the complex self-organizing processes in non-living systems might reflect this same fundamental principle.

This isn't mystical thinking—it's logical necessity. If motion exists (and clearly it does), and if communicated motion requires self-motion as its ultimate source (which the argument demonstrates), then self-motion must be the foundation of all movement in the universe.

Modern Echoes

Interestingly, modern physics hasn't entirely resolved this ancient puzzle. Newton's first law tells us that objects in motion stay in motion unless acted upon by a force—but it doesn't explain where motion comes from in the first place. Quantum mechanics reveals that even "empty" space seethes with spontaneous activity. Biological systems exhibit emergent properties that seem to transcend their mechanical components.

The ancient argument doesn't contradict modern science; it asks a different kind of question. While physics describes how motion behaves, philosophy asks why motion exists at all and what makes self-initiated movement possible.

Living the Logic

So what does this mean for your daily life? Every time you make a choice—to smile at a stranger, to learn something new, to change direction in your career—you're exercising the same principle the ancients called soul. You're demonstrating that you're not just a passive link in a chain of mechanical causation, but a source of genuine self-motion.

This perspective can be profoundly empowering. It suggests that your capacity for self-initiated action connects you to the fundamental creative principle of the universe. When you move yourself—whether physically, mentally, or spiritually—you're participating in the same force that keeps planets spinning and hearts beating.

The next time you watch that child push a toy car, remember: you're witnessing not just the transfer of mechanical energy, but the expression of self-motion through communicated motion. The child's decision to play, the life force animating their muscles, the creative spark behind their imagination—all of these represent the soul-principle that the ancient argument reveals as the source of all movement.

Perhaps the most beautiful insight from this ancient logic is that motion isn't just something that happens to us—it's something we participate in creating, moment by moment, choice by choice.

What moves you to move? And in your daily choices, how do you experience the difference between being pushed by external forces and moving from your own inner source?